” IF WE HAVE A PULSE, WE HAVE A PURPOSE.”

Unknown

After working with a Pain Management doctor for six months he’s determined I’m a good candidate for a Spine Stimulator. It works by leads placed in your mid-back attached to the implanted stimulation device, the stimulation disrupts the pain signals to the brain thus relieving the pain. I had my psychological evaluation yesterday and now waiting for insurance approval. My hope is to have the trial surgery in early February.

Melinda

I’m so glad you stopped by today. I appreciate you and so glad to be a part of your day. Melinda

Your prompt for #JusJoJan and Stream of Consciousness Saturday is: “last call.” Talk about the enterprise (sales or service) conducted by the last phone call you received from a business you’re not associated with (i.e. your workplace), or talk about that phone conversation itself. Have fun!

There was a time when “last call” was a total bummer and often meant an end to a fun night of drinking. After 15 years of sobriety and not being in a bar at that hour the prompt “last call” didn’t get any reaction. There is a famous sale at Neiman Marcus called Last Call and you know about even if you don’t shop there.

It’s a great time to pick through all the high end goods looking for that can’t pass up buy. I find myself looking for the diamond in the rough at below cost prices. Like most retail it’s not really a “last call’ it’s more of a siren to pull shoppers in.

Have a great weekend. Thanks for reading, I appreciate you.

Melinda

Here are the rules for SoCS:

IDEAS.TED.COM

Sep 23, 2019 / Jeffrey Chen, MD

iStock

CBD gummies. CBD shots in your latte. CBD dog biscuits. From spas to drug stores, supermarkets to cafes, wherever you go in the US today, you’re likely to see products infused with CBD. There are cosmetics, vape pens, pills and, of course, the extract itself; there are even CBD-containing sexual lubricants for women which aim to reduce pelvic pain or enhance sensation. CBD has been hailed by some users as having cured their pain, anxiety, insomnia, depression or seizures, and it’s been touted by advertisers as a supplement that can treat all of the above and combat aging and chronic disease.

As Executive Director of the UCLA Cannabis Research Initiative, I’m dedicated to unearthing the scientific truth — the good and the bad — behind cannabis and CBD. My interest was sparked in 2014 when I was a medical student at UCLA, and I discovered a parent successfully treating her child’s severe epilepsy with CBD. I was surprised and intrigued. Despite California legalizing medical cannabis in 1996, we weren’t taught anything about cannabis or CBD in med school. I did research and found other families and children like Charlotte Figi reporting success with CBD, and I knew it was something that needed to be investigated. I established Cannabis Research Initiative in the fall of 2017, and today we have more than 40 faculty members across 18 departments and 8 schools at UCLA working on cannabis research, education and patient-care projects.

So what exactly is CBD and where does it come from? CBD is short for cannabidiol, one of the compounds in the cannabinoid family which, in nature, is found only in the cannabis plant (its official scientific name is Cannabis sativa l.). THC — short for tetrahydrocannabinoid — is the other highly abundant cannabinoid present in cannabis that’s used today. THC and CBD exert their effects in part by mimicking or boosting levels of endocannabinoids, chemical compounds that are naturally produced by humans and found throughout our bodies. Endocannabinoids play an important role in regulating mood, memory, appetite, stress, sleep, metabolism, immune function, pain sensation, and reproduction.

Despite the fact that they’re both cannabinoids found only in the cannabis plant, THC and CBD are polar opposites in many ways. THC is intoxicatingand responsible for the “high” of cannabis, but CBD has no such effect. THC is addictive; CBD is not addictive and even appears to have some anti-addictive effects against compounds like opioids. While THC stimulates the human appetite, CBD does not. There are areas where they overlap — in preliminary animal studies, THC and CBD exhibit some similar effects, including pain-relieving and anti-inflammatory properties and anti-oxidant and neuroprotective effects. In some early research, they’ve even shown the ability to inhibit the growth of cancer cells, but years of rigorous studies need to be conducted before we’ll know whether they have the same impact on humans.

Even though humans have been using cannabis for thousands of years, the products available today are not the cannabis that has traditionally been consumed. After cannabis was prohibited at the federal level in 1970 by the US Controlled Substances Act, illicit growers were incentivized to breed strains that had higher amounts of THC, so they could increase their profits without needing larger growing spaces. What they didn’t know was that by driving up THC content, they were dramatically reducing the CBD content. In 1995, after decades of surreptitious breeding, the ratio of THC to CBD was ~15:1, and by 2014 the ratio had jumped to ~80:1 as CBD content further plummeted.

Due to decades of research restrictions in the US and growers’ focus on THC, there are very few human studies that look at CBD and its effects. The strongest evidence we have is that CBD can reduce the frequency of seizures in certain rare pediatric disorders — so much that a CBD-based drug called Epidiolex was FDA-approved in 2018 for this purpose. There is also preliminary human data from small clinical trials with dozens of subjects that suggests CBD may have the potential to be used for conditions like anxiety, schizophrenia, opioid addiction, and Parkinson’s disease. But please note that the participants in these studies generally received several hundreds of milligrams of CBD a day, meaning the 5mg to 25mg of CBD per serving in popular CBD products may likely be inadequate. And even if you took dozens of servings to reach the dosage used in these clinical trials, there is still no guarantee of benefit because of how preliminary these findings are.

But while there is a lack of concrete and conclusive evidence about CBD’s effects, there is considerable hope. Recent legislative changes around hemp and CBD in the US and across the world have enabled numerous human clinical trials to begin, investigating the use of CBD for conditions such as autism, chronic pain, mood disorders, alcohol use disorder, Crohn’s disease, graft-versus-host-disease, arthritis and cancer- and cancer-treatment-related side effects such as nausea, vomiting and pain. The results of these studies should become available over the next five years.

Furthermore, in an effort to protect consumers, the FDA has announced that it will soon issue and enforce regulations on all CBD products. Buyers should beware because the products being sold today may contain contaminants or have inaccurately labelled CBD content — due to the deluge of CBD products on the market, government agencies haven’t been able to react quickly enough so there is currently no regulation in the US whatsoever on CBD products.

While CBD appears to be generally safe, it still has side effects. In children suffering from severe epilepsy, high doses of CBD have caused reactions such as sleepiness, vomiting and diarrhea. However, we don’t know if this necessarily applies to adults using CBD because these children were very sick and on many medications, and the equivalent dose for an average 154-pound adult would be a whopping 1400 mg/day. And while CBD use in the short term (from weeks to months) has been shown to be safe, we have no data on what side effects might be present with chronic use (from months to years).

Right now, the most significant side effect of CBD we’ve seen is its interaction with other drugs. CBD impacts how the human liver breaks down other drugs, which means it can elevate the blood levels of other prescription medications that people are taking — and thus increase the risk of experiencing their side effects. And women who are pregnant or who are expecting to be should be aware of this: We don’t know if CBD is safe for the fetus during pregnancy.

So where does this leave us? Unfortunately, outside of certain rare pediatric seizure disorders, we scientists do not have solid data on whether CBD can truly help the conditions that consumers are flocking to it for — conditions like insomnia, depression and pain. And even if it did, we still need to figure out the right dose and delivery form. Plus, CBD is not without side effects. Here’s the advice that I give to my friends and family: If you’re using CBD (or thinking about using it), please research products and talk to your doctor so they can monitor you for side effects and interactions with any other drugs you take.

So is CBD a panacea or a placebo? The answer is: Neither. CBD is an under-investigated compound that has the potential to benefit many conditions. While it does have side effects, it appears as if it could be a safer alternative to highly addictive drugs such as opioids or benzodiazepines. And thanks to a recent surge in research, we’ll be learning a lot more about its capabilities and limits in the next five years.

Watch his TEDxPershingSq talk now:

Jeffrey Chen, MD , is the founder and Executive Director of the UCLA Cannabis Research Initiative where he leads an interdisciplinary group of 40+ UCLA faculty conducting cannabis related research, education and patient care. You can follow him @drjeffchen or visit his website http://www.drjeffchen.com.

IDEAS.TED.COM

Jan 14, 2020 / Meik Wiking

Jared Oriel

Ask any older person to recall some of their memories, and there’s a good chance they will tell you stories from when they were between the ages of 15 and 30. This is known as the reminiscence effect, or reminiscence bump.

Memory research is sometimes conducted by using cue words. If I say the word “dog,” what memory comes to mind? Or “book’? Or “grapefruit’? It’s best to use words that are not related to a certain period in life. For instance, the phrase “driver’s license” is more likely to prompt memories from when you were a specific age than the word “lamp.”

In studies, when participants were shown a series of cue words and asked about the memories they associate with those words and how old they were at the time of the memory, their responses will typically produce a curve with a characteristic shape, the reminiscence bump. The recency effect — a final upward flip of the curve — can usually be seen, too. For example, when asked what memory comes to mind when cued with the word “book,” what people have read recently may pop up more easily than what they read 10 years ago.

You can also see the reminiscence effect in some autobiographies, where adolescence and early adulthood are described over a disproportionate number of pages. If you look at Agatha Christie’s autobiography, which is 544 pages long, the death of her mother happens on page 346, when Christie was 33. In the period that covers the reminiscence bump in her life, memories fill more than 10 pages per year. In contrast, she sums up the events of 1945 to 1965, when she was aged between 55 and 75, in just 23 pages — a little over one page per year.

What do you remember about being 21, or from another year? And how do your memories from different decades compare?

One theory behind the reminiscence bump is that our teens and early adulthood years are our defining years, our formative years. Our identity and sense of self is developing at that time, and some studies suggest that experiences linked to who we see ourselves as are more frequently retold in explaining who we are and are therefore remembered better later in life.

One study found that 73 percent of people’s vivid memories were either first-time experiences or unique events.

Another theory is that the period involves a lot of firsts. Our first kiss, our first flat, our first job. In the Happy Memory Study we conducted at the Happiness Research Institute, we found that 23 percent of people’s memories were of novel or extraordinary experiences.

Novelty ensures durability when it comes to memory. Several studies show that we are better at remembering the novel and the new, the extraordinary days when we did something different. One study by British researchers Gillian Cohen and Dorothy Faulkner found that 73 percent of vivid memories were either first-time experiences or unique events. Extraordinary and novel experiences are subject to greater elaborative cognitive processing, which leads to better encoding of these memories. That is the power of firsts. Extraordinary days are memorable days.

The importance of firsts also means that, say, if you go to university, you are more likely to remember events from the beginning of your first year than later in that same year. In a study led by David Pillemer, professor of psychology at the University of New Hampshire, participants were asked to describe memories from their freshman year in college. “We are not interested in any particular type of experience,” said the researchers, “just describe the first memories that come to mind.” The researchers interviewed women who had graduated 2, 12 or 22 years ago from Wellesley College in Massachusetts.

In the second part of the study, participants were asked to analyze, one by one, each of the memories they had described earlier. The memories were rated on the intensity of the emotions the experience involved, the impact the event had on their life (both at the time of the memory and also in retrospect), and the estimated date of the experience they remembered.

The study showed that the majority of memories took place at the beginning of the academic year: around 40 percent in the month of September and around 16 percent in October. These results suggest that transitional and emotional experiences are especially likely to persist in the memory for many years. That is the power of firsts.

In our study, we also found evidence of the power of extraordinary days and novel experiences when it comes to happy memories. That is why I remember every first kiss I’ve ever had — including the very first.

In our study, we also found evidence of the power of extraordinary days and novel experiences when it comes to happy memories. More than 5 percent of all the happy memories we collected are explicitly about firsts. First dates, first kisses, first steps — or traveling alone to Italy at the age of 60 for the first time. The first job, the first dance performance or the first time you watched a movie in the cinema with your dad.

That is why I remember every first kiss I’ve ever had — including the very first. Her name was Kristy and I was 16 and scared of her dad, who was a professional rugby player.

If you want to create a night to remember for dinner guests, serving them something they have not tasted before might do the trick.

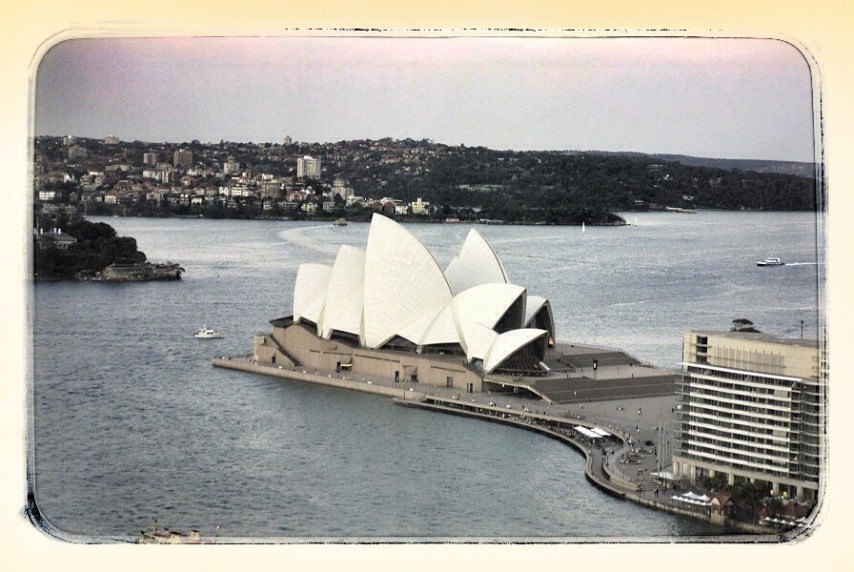

New and memorable experiences can also come in the form of food. I was 16 when I first tasted a mango. It was in 1994, I was an exchange student in Australia, and mangoes had not yet been introduced to supermarkets in Denmark, where I grew up.

I remember the sweetness, the texture. I remember thinking, “Where have you been all my life?” Since then, I have been chasing mangoes — other great food experiences out there which I have not yet had. I have tried fermented Icelandic shark and snails in a street market in Morocco. Both made me throw up a little, but I remember those moments quite vividly.

My point is that firsts can come in the shape of gastronomy. If you want to create a night to remember for your dinner guests, serving them something they have not tasted before might do the trick (but maybe not fermented shark, if you want them to come again). Ideally, it would be something that is not over and done with in a second, like a shot of licorice vodka at 3 AM. Nobody remembers that — for several reasons.

Better to go with something like an artichoke, which takes a bit of an effort to eat, as you have to peel each leaf off, dip it in salted butter, then use your teeth to harvest that wonderful flesh. This makes the whole experience longer lasting and multisensory.

It might also be the reason why life seems to speed up as we get older. When we’re in our teens, there are a lot of firsts, while firsts at age 50 are rarer. This is also why studies find that people who immigrated from a Spanish-speaking country to the US have their reminiscence bump at different times, depending on how old they were at the time of the move. Temporal landmarks of firsts and changes of scene play an important role in organizing autobiographical memory. There is a before and an after.

If we want life to slow down, to make moments memorable and our lives unforgettable, we may want to remember to harness the power of firsts. In our daily routines, it’s also an idea to consider how we can turn the ordinary into something more extraordinary in order to stretch the river of time. It may be little things. If you always eat in front of the television, it might make the day feel a little more extraordinary if you gather for a family dinner around a candlelit table—and if you are always eating candlelit dinners, it might be nice to eat dinner during a movie marathon.

Adapted from the new book The Art of Making Memories: How to Create and Remember Happy Moments by Meik Wiking. Published by William Morrow. Copyright © 2019 by Meik Wiking. Reprinted courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers.

Watch his TEDxCopenhagen talk here:

Meik Wiking is CEO of the Happiness Research Institute, research associate for Denmark at the World Database of Happiness, and founding member of the Latin American Network for Wellbeing and Quality of Life Policies. He is the author of The Little Book of Hygge, and he lives in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Have a great day, I so glad you stopped by today. Melinda

| Dear friends, “Beyond Survival: Hope and Healing on Kilimanjaro” is the 11th addition to the MenHealing library of videos that feature the healing journeys of male survivors. This 22-minute video chronicles the incredible journey of Weekend Of Recovery Alumnus Jordan Masciangelo’s successful climb to the 19,341 foot summit of Africa’s Mt. Kilimanjaro In January 2019 This Expedition Climb project was a labor of love to heighten public awareness about male sexual victimization and was successful in raising nearly $9,500 for the WOR Scholarship Fund. We are deeply grateful to David James Findlay, a professional television commercial editor in Toronto, for producing this video FOR FREE as a gift to Jordan and to MenHealing. To watch the video click here.  All “Beyond Survival: Voices of Healing” videos now have closed caption accessibility. Several videos are also currently available with Spanish language access; Spanish translation for all videos will be completed soon. All “Beyond Survival: Voices of Healing” videos now have closed caption accessibility. Several videos are also currently available with Spanish language access; Spanish translation for all videos will be completed soon.Jim Struve Executive Director, MenHealing/Weekends of Recovery www.menhealing.org Stay connected on our social media platforms! |

| MaleSurvivor.org, 4768 Broadway #527, New York City, NY 10034-4916SafeUnsubscribe™ survivors14@Verizon.netForward this email | Update Profile | About our service providerSent by outreach@malesurvivor.org in collaboration withTry email marketing for free today! |

Looking For The Light is a proud member of the Chronic Illness Bloggers Network. I joined six months ago and want to remind others who may be interested in joining or utilizing the resources they have available.

If you suffer from a Chronic Illness and want more information or to join, you can find us at http://www.chronicillnessbloggers.com.

By Bethany Bray

Licensed professional counselor (LPC) Ruth Drew oversees the Alzheimer’s Association’s 24-hour helpline, which offers support to those facing the challenges of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, including families and caregivers. The fact that the helpline receives more than 300,000 calls each year hints at the heart-wrenching issues that accompany a dementia diagnosis, not just for the individual but for the person’s entire support system.

“We receive a wide range of questions, from someone worried about the warning signs of cognitive decline or dealing with a new diagnosis, to an adult son whose mother didn’t recognize him for the first time, or a wife wondering how to get her husband with Alzheimer’s to take a bath. Whatever the reason for the call, we meet callers where they are and endeavor to provide the information, resources and emotional support they need,” says Drew, director of information and support services at the Chicago-based nonprofit.

Professional counselors are a good fit to help not only individuals with dementia and Alzheimer’s, but also those in their care networks, Drew says. Whether counseling individuals, couples or even children, the far-reaching implications of dementia mean that practitioners of any specialization may hear clients talk about the stressors and overwhelming emotions that can accompany the diagnosis.

“People diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and other dementia diseases are going through profound life changes — coping with the realities of an incurable disease that is stealing their abilities and their memories. Counseling offers a place to process the losses, develop ways to cope, and find meaning in their current situation,” Drew says. “Similarly, family members face emotional, physical and financial challenges when they care for someone with Alzheimer’s. It helps to have a safe place to process feelings, get support, learn to cope with present realities, and plan for the future.”

A growing need

“Dementia isn’t a normal part of aging. It just happens that most dementia patients are older,” says Jenny Heuer, an LPC and certified dementia practitioner in Georgia who specializes in gerontology. “There is this stigma that just because you’re getting older, you’re going to get dementia.”

The Alzheimer’s Association (alz.org) defines dementia as “an overall term for diseases and conditions characterized by a decline in memory, language, problem-solving and other thinking skills that affect a person’s ability to perform everyday activities.”

Although many people associate dementia with Alzheimer’s, there are numerous forms of dementia, and not all are progressive. Dementia can be reversible or irreversible, depending on the type, explains Heuer, the primary therapist in the geriatric unit at Chatuge Regional Hospital in Hiawassee, Georgia. Alzheimer’s, an irreversible, progressive form of dementia, is most common, followed by vascular dementia, which can occur after a stroke. Forms of dementia can also co-occur with Down syndrome, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease and other diagnoses. Research has also linked moderate to severe traumatic brain injury to a higher risk of developing dementia or Alzheimer’s disease years later.

Heuer, a member of the American Counseling Association, recalls a client she counseled who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s prior to age 62. She had lived with a husband who was violent and physically abusive toward her, and the client’s caregivers wondered if she had suffered a brain injury that contributed to her early onset Alzheimer’s.

Heuer notes that other conditions can lead to an assumption or misdiagnosis of dementia. For example, a urinary tract infection (UTI), if left untreated, can progress far enough to cause confusion in a client. Once the UTI is diagnosed and treated, the confusion can dissipate. In addition, excessive alcohol use, depression, medication side effects, thyroid problems, and vitamin deficiencies can cause memory loss and confusion that could be mistaken for dementia, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

“There’s so many [other] things to rule out,” Heuer says. “Doctors try to rule out every other health issue before they diagnose dementia.”

The complicated nature of dementia only reinforces the need for counselors to do thorough intake evaluations and to get to know clients holistically, Heuer says. Counselors should ask clients about anything that has affected or could be affecting their brain or memory, including medication use, stress levels, past physical trauma or brain injury, depression, sleep patterns, exercise and other factors.

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that roughly 50 million people worldwide currently have dementia, and nearly 10 million new cases develop each year. Alzheimer’s disease-related dementia may contribute anywhere from 60% to 70% of that overall number, according to WHO.

Alzheimer’s is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Alzheimer’s Association estimates that 14% of people ages 71 and older in the United States have some form of dementia. A recent report from the nonprofit estimated that 5.7 million Americans of all ages were living with Alzheimer’s-related dementia in 2018, the vast majority of whom (5.5 million) were 65 and older. Close to two-thirds of Americans with Alzheimer’s disease are women, according to the association.

These numbers are only expected to increase as the U.S. population ages and the baby-boom generation reaches retirement and later life, Heuer notes.

The U.S. Census Bureau projects that in the year 2034, the number of Americans 65 and older will, for the first time in history, eclipse the nation’s number of youths under age 18. By 2060, close to one-quarter of Americans will be 65 or older, and the number of people older than 85 will have tripled.

“Aging issues hit home for counselors across the board,” Heuer says, “because we are all aging, and many are caring for aging parents. … I invite other counselors to join me in working with this population. [Alzheimer’s] is the sixth-leading cause of death. That sounds very morbid, but it’s only going to go higher. More and more people will be diagnosed. With the aging baby-boom population, there’s someone around every corner [who is] going to be impacted by this disease.”

Caring for the caregivers

There is an obvious emotional component to caring for a loved one affected by memory loss and the other aspects of dementia, but there is also the burden of assuming management of the person’s practical tasks, such as financial planning and keeping up with medical appointments. The stress of it all can affect the person’s entire network, says Phillip Rumrill, a certified rehabilitation counselor in Ohio whose professional area of expertise is clients with disability, including dementia.

“Dementia affects the whole family system, and possibly for generations. The person [with dementia] needs help, yes, but [so do] their spouse, children and entire family system. That’s critically important [for counselors to be aware of] when you’re dealing with dementia,” says Rumrill, a member of the American Rehabilitation Counseling Association, a division of ACA. “There is a tremendous amount of burnout that comes with being a dementia caregiver.”

Witnessing a loved one’s memory and abilities decline can cause caregivers to feel sad, frustrated, exhausted, overwhelmed, hurt, afraid and even angry, says Matt Gildehaus, an LPC who owns Life Delta Counseling, a private practice in Washington, Missouri.

“The caregivers and loved ones are often the hidden victims of dementia. They can become completely overwhelmed as the role becomes all-encompassing,” says Gildehaus, who counsels adults facing a range of challenges, including aging-related issues and dementia. “Taking care

of someone can easily become an identity that gets affirmed and reinforced until it comes at nearly the complete expense of self-care. When being the caregiver for someone with dementia overtakes their life, the caregiver’s emotional and physical health frequently begin to decline.”

Each of the counselors interviewed for this article asserted that clinicians should, first and foremost, emphasize the importance of self-care with clients who are caregivers to individuals with dementia. Counselor clinicians can ask these clients what they are doing for self-care, help them establish a self-care plan if needed, and connect them with local resources such as support groups and eldercare organizations.

It is also important to encourage clients to ask for help from others when they are becoming overwhelmed, says Rumrill, a professor and coordinator of the rehabilitation counseling program at Kent State University in Ohio, as well as founding director of its Center for Disability Studies. If clients mention having a loved one with dementia, counselors should listen carefully to make sure these clients are taking care of themselves and processing their feelings related to the experience.

Connecting clients to support groups and other resources can be vital because many families feel lost and isolated after their loved one receives a dementia or Alzheimer’s diagnosis, Drew notes. “This isolation can increase throughout the journey as caregiving demands intensify, especially if they don’t know where to turn for help,” she says.

Families may also experience emotions that parallel the grieving process as they witness the progressive loss of the person they knew. Caregivers might even find themselves with hard feelings emerging toward their loved one, particularly as they try to handle the frustrating behavior challenges that Alzheimer’s and dementia can introduce.

“The disease can be very deceiving because one day the person may be very clear, and another day they’ll be confused. Caregivers can feel [the person is] doing things on purpose, just to push their buttons,” Heuer says. “I often ask if the person was aggressive or called [the client] names before they were diagnosed. Most often, the answer is no. Then I explain that it’s the disease, not the individual” prompting the behavior.

Gildehaus, a member of ACA, has seen similar frustrations among clients in his caseload. “I often help caregiver clients by providing a safe place for them to share the things they don’t feel they can share with family and friends,” he says. “For caregivers, there are three tools I focus on using: therapeutic silence, empathic listening, and normalizing what they often describe as ‘terrible thoughts.’ These … can be ideas like, ‘They make me so angry,’ ‘I dread going to the nursing home some days’ or even ‘Sometimes I secretly hope they don’t live for years like this.’”

Rumrill notes that clients caring for a loved one with dementia may need a counselor’s help to process how the disease has disrupted roles within the family. He experienced this personally when caring for his grandmother, who lived with dementia for years before passing away in 2009 of stomach and liver cancers. Rumrill, who held power of attorney for his grandmother’s financial affairs, had to adjust to taking care of someone who had taken care of him throughout his life. It felt like a role conflict to have to begin making decisions on his grandmother’s behalf while still trying to respect her wishes, he recalls.

“It’s changing roles: They used to take care of you, and now you take care of them,” Rumrill says. “There is an odd juxtaposition when a child is telling a parent what to do. It can be hard [for the older adult] to accept when it’s coming from the younger generation. The roles have switched, and no one got the memo.”

Counseling sessions for couples and families can also serve as safe spaces to talk through the stressors and disagreements that come with caregiving, Rumrill and Heuer note. Counselors can serve as neutral moderators to facilitate conversations about tough subjects that clients may be fearful of or avoiding outside of sessions. This can include talking over logistical or financial issues, such as dividing caregiving tasks or assigning power of attorney, and harder conversations such as when and how to move a loved one to a care facility.

Counselors who work with couples should be aware of the intense stress that providing care for someone with dementia can put on relationships, Rumrill adds. Home life can be turned upside down when one member of a couple’s time and attention are devoted to caregiving. This is especially true if the family member with dementia moves into the home. Tasks that used to flow easily, such as unloading the dishwasher or taking the kids to sports practices, can become points of contention. Challenges that the couple successfully navigated before — from budgeting to parenting issues — can become more pronounced and complicated as caregiving puts extra strain on the couple’s time, emotions and finances, Rumrill says.

It’s an unfortunate reality, but counselors working with clients who have dementia or their families also need to be watchful for signs of elder abuse, including financial abuse, Rumrill says. Dementia patients and their caregivers are also at higher risk for issues such as depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and substance use and abuse (which may be used as a coping mechanism).

Listen and validate

Clients who have dementia can get a variety of needs addressed in counseling sessions — needs that will change as the dementia progresses.

In the early stages of dementia, counselors can help clients process their feelings and fears about the diagnosis, as well as work toward accepting and adapting to the changes that are coming. In the middle to latter stages, clients may benefit more from reassurance and validation from a counselor, as well as occasional redirection and calming techniques.

Heuer recalls a client whose husband had recently been placed in a memory care facility because of Alzheimer’s disease. The client — whom Heuer calls “Anne” for the purposes of this example — was dealing with pre-existing depression, which was the initial focus of the counseling sessions. Heuer and Anne also discussed Anne’s relationships with family members and the various changes she was facing, which included moving because of her husband’s placement in the memory care facility.

According to Heuer, Anne harbored a great fear of losing her own memory, and over time, her memory did in fact begin to deteriorate. She would acknowledge the decline in counseling sessions as she and Heuer talked about its impact on Anne’s life. Later, as Anne’s dementia progressed, Heuer shifted her work to focus more on fostering Anne’s feelings of safety and connection. “The interesting part of working with Anne is she never mentioned the word dementia. I heard about her diagnosis from family and caregivers,” Heuer recalls.

“As her memory declined, I would reflect her feelings [in counseling],” Heuer says. “Then there were sessions where Anne would spend the majority of the time talking about how she had been traveling on a train and had just gotten off the train. Frequently, she would share the story as if it was the first time she was telling it to me.” Heuer says one of the best suggestions she has been given for working with clients with dementia is to show them the same level of patience and attention regardless of whether they are telling her a story or sharing a memory with her for the first time or the 10th time.

“Anne also had hallucinations [in the latter stages of dementia],” Heuer says. “She had moments of clarity where she knew they were hallucinations and questioned her own sanity. I had no magical cure or answer. I would try and imagine how I would feel if this were happening to me and [then] tapped into empathy and the core foundation of person-centered therapy.”

Most of all, individuals with dementia need a counselor to simply “be present and listen,” adds John Michalka, an LPC with a solo private practice in Chesterfield, Missouri. He specializes in working with clients who have mood disorders related to chronic illness, including dementia.

“Patients living with dementia often tell me they just need their loved ones to stop nagging them and making them feel like the things they are doing are intentional,” says Michalka, an ACA member who has personal experience caring for a loved one with dementia. “The patient isn’t forgetting on purpose. The patient has enough to deal with without being made to feel like a burden as well. It always amazes me how simple and unselfish the patient’s request is when it comes to what they need: just simple love, understanding and patience.”

The following insights may be helpful for counselors who treat clients with dementia. Some of the guidance may also be relevant to share with clients who are family members of or caregivers to a person with dementia.

>> Correcting versus agreeing: Patients in the memory care unit where Heuer works sometimes come up to her and say, “It’s so good to see you again!” even though they have never met her before. Over time, she has learned to read clients and think on her feet to respond appropriately to remarks that aren’t based in reality.

For caregivers, deciding whether to correct a person with dementia or go along with what the person is saying can become a daily or even moment-to-moment struggle. Heuer says her decision to validate or correct is often based on how likely the person is to become agitated or aggressive. But empathy also comes into play. “I try to put myself in their shoes. How would I feel if I were seeing a friend I hadn’t seen in a while? It really comes down to meeting them in their emotions.”

Some clinicians may call the practice of validating or going along with a client with dementia “therapeutic lying,” Heuer says, but “I call it ‘molding the information’ and doing what it takes for them to feel calm and safe. …We have to adapt to them because they are not able to adapt to us. It is as if they have a different inner world, and we have to meet them in their world.”

Michalka says he also finds validation therapy helpful for easing anxiety in clients. With clients who are dementia caregivers, he often emphasizes that what is going on in the mind of the person with dementia is their reality.

He recalls one client who was beginning to panic because they saw someone in their room. “There was no one in the room, but the patient’s experience or perception of a stranger in their room was real,” Michalka says. “A natural reaction for most caregivers would be to correct the patient. In doing so, we are challenging the patient’s perception of reality. This typically will only escalate the patient’s anxiety and, in doing so, escalate the loved one’s or caregiver’s anxiety.

“Imagine if you saw a stranger in your room, and when you [try] to tell someone, they proceed to tell you, ‘No, there [isn’t].’ Would you not become more and more agitated as you try to convince them [and] they continue to challenge your reality? Instead, we should validate their experience by asking if that stranger is still in the room. Then, one would empathize with the patient by validating how scary that must have been, but now the stranger is no longer there and they are safe. After which, the patient’s attention should be redirected to a more pleasant thought or situation.”

>> Considering the whole person: Working with clients with dementia “takes you out of your comfort level because you have to become very creative in how you interact with [them]. It’s not the type of counseling that you learn in a textbook,” Heuer says. “Your ability to counsel and work with these individuals goes well beyond the knowledge you gain about counseling in your master’s [program].”

Heuer encourages clinicians to learn more about who clients were before their dementia diagnosis — what they did for a career, what their hobbies were, their likes and dislikes. Counselors can ask clients directly for this personal information or seek details from their family members. Learning these personal details can help to better inform counselors’ interventions and help form stronger connections with clients, Heuer says. “Tapping into what made them happy as a human being [without dementia] may be therapeutic for them,” she adds.

For example, a client who loves baseball may be comforted and more responsive while watching a televised ballgame or flipping through an album of baseball cards with a counselor. A client who was a teacher or a banker might find comfort writing in a ledger. Even clients with late-stage dementia can respond when their favorite music is played, Heuer notes.

She recalls one client who had previously worked in business and would sometimes think that his caregiver was his secretary. When this happened, the caregiver would “take notes” for him by writing on paper. “It doesn’t have to make sense, but to them it may make sense,” says Heuer, whose doctoral dissertation was on the lived experiences of individuals with early stage Alzheimer’s disease.

>> Redirecting: When working with clients in the middle to latter stages of dementia, techniques that prompt a change of focus are invaluable. Redirection can keep these clients from becoming upset or escalating to aggression, Heuer says. For caregivers, this technique might involve engaging the person in an activity that they used to enjoy or simply asking for help with a task, such as folding laundry or setting the table.

“Redirection really comes into play when an individual is exhibiting behaviors such as agitation, fear, anger or paranoia,” Heuer explains. “Normally, there is something in their environment that is triggering them. An example we often observe and hear about is an individual [who] is wanting to go home. In essence, they want to feel safe and are looking for something familiar. Redirection is a technique that refocuses the individual’s attention in an effort to therapeutically calm them and make them feel safe.”

Heuer mentions a woman who was wandering in the care facility where Heuer works and feeling a strong urge to leave. The woman was getting agitated and escalating to the point that staff members were going to medicate her. Heuer stepped in and asked the woman if she wanted to take a walk. The woman agreed and soon calmed down as she and Heuer walked together and chatted.

With dementia, behaviors often manifest out of the person’s worry about their own safety or the safety of loved ones, Heuer notes.

“We all have that need to have a sense of purpose. Just because someone has dementia, they’re not less human. They have similar needs but have a different way of communicating them. Usually, there is a need behind every single behavior they’re displaying,” Heuer says.

>> Working through grief: Individuals with dementia and their loved ones often experience a range of grief-related emotions, from denial and avoidance to sadness. Counselors may find it helpful to use grief and loss techniques with these clients, Rumrill says.

Watching a loved one with dementia decline and seemingly change into a different person can feel similar to experiencing that person’s death or loss, Rumrill says. In the case of his grandmother, even her vocabulary and the way she spoke changed. She began using profanity and other words that Rumrill wasn’t previously aware she even knew. When she became angry, Rumrill says she would “go off” on people, which she never did prior to her dementia diagnosis.

“There’s a tremendous sense of loss that can go with that. The person you knew and loved isn’t there [any longer],” he says. “I was grieving the loss of who [his grandmother] was and also grieving with her over her loss of independence.”

Feelings of loss can also resurface for clients with dementia who are widows or widowers, even if they have previously processed their partner’s death. Dementia can reaggravate the person’s feelings of grief and sadness or even ignite feelings of anger toward a deceased partner for leaving them to go through their dementia journey alone, Rumrill says.

Family members and caregivers may experience repeated cycles of grief as their loved one’s dementia or Alzheimer’s progresses, Michalka adds. “Each time the loved one living with dementia progresses to the next stage, the client [a caregiver or family member] in some ways repeats the grieving process. They now are experiencing another loss. It is as if they have lost their loved one once again,” Michalka says. “It is extremely difficult for many clients to have mom or dad not know who they are or simply not remember their name. The client loses their loved one many times during the progression of dementia. At a minimum, the client loses the person their loved one once was, and then once again upon the passing of the loved one.”

>> Focusing on strengths: Clients with dementia are likely to be saddened by the anticipated or actual loss of their abilities. A counselor can help these clients flip their perspective to focus on what the person can still do, Heuer says. She often uses the words strengths and challenges, not weaknesses, during conversations about what the client is still able to do and enjoy.

For example, a client with dementia may no longer be able to maintain a garden outdoors, but gardening supplies and planter pots can be brought to the person inside so they can still get their hands in the soil. “Activities can change as the disease progresses,” Heuer notes.

>> Using “tell me about” prompts: Gildehaus says that narrative therapy can be a helpful technique with clients who have dementia. These clients often respond well to storytelling prompts, even as their memories fade. It can be therapeutic for clients with dementia to share memories and, in turn, to feel heard and understood, he explains.

Similarly, Heuer uses reminiscence therapy with clients with memory loss, asking individuals to talk about their careers, families, and other favorite memories. It is not helpful, however, to frame questions by asking clients whether they remember something, she stresses. Instead, counselors can use gentler “tell me about” prompts to spur clients to open up. For example, instead of asking, “Do you remember your parents?” a counselor would say, “Tell me about your parents,” Heuer explains.

Rumrill notes that group work can be very helpful for caregivers or family members of people with dementia, especially to prevent or ease burnout. Motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioral techniques, and rational emotive techniques can also help clients process the changes and stresses that come with having a loved one with dementia. But Rumrill urges counselors to use whatever techniques they find to be most helpful to and best suited for the client.

Dementia is “no more stressful than any other life issue that brings people to counseling; it’s just different,” Rumrill says. “It has unique features that need to be understood to help. Marshal all the coping reserves you can to help the client.”

>> Offering empathic listening: Gildehaus notes that professional counselors’ core skills of listening, empathic reflection and normalization can go a long way for clients dealing with dementia.

“In my experience, clients struggling with dementia need someone to listen to them for understanding without confronting them, trying to argue with them, or trying to fix them,” Gildehaus says. “Normalizing frustrations and fears related to memory challenges and aging also helps clients feel less defective.”

When working with clients who have dementia, Gildehaus says his primary objective is to offer a nonjudgmental environment in which these individuals can share their frustrations and fears. “My efforts are focused on providing an interaction where they feel heard and understood without feeling questioned or having someone trying to talk them out of their ideas,” he says.

This came into play this past summer as Gildehaus faced a tough conversation with a client who needed to give up her right to drive because of cognitive decline. “This was very hard for her,” he recalls. “She argued that she did not drive far, that she had not had any accidents, and that she didn’t care if she died in an accident. She became very emotional — tearful and angry. I listened empathically, validated her truths, and reflected her logic and feelings. Then, I asked if she wanted her lasting legacy to be causing someone else’s injury or death. She agreed this was not what she wanted. We then explored options and resources that would allow her to maintain her freedom and active schedule without driving. We talked about local taxi services, friends who were going to the same activities [and could give her a ride], and the obvious solution became allowing her home health care provider to drive her most of the time.”

Still human

Individuals with a dementia diagnosis often feel as if they’ve been labeled as damaged goods, “deemed incompetent and unable to do anything for themselves,” Heuer says. The empathy and support that professional counselors are capable of offering these clients can go a long way toward changing that mindset, she asserts.

People with dementia “are still capable, still human, and they have emotions,” Heuer emphasizes. “There is an immediate stigma attached to someone [with a dementia diagnosis] that they aren’t able to do anything for themselves, and that’s often a source of frustration. There is an assumption that they’re helpless. But they will say, ‘I need help.” … They will let you know. What they need from counselors — and everyone else — is the recognition that they are still a person and still human.”

****

Counselors as caregivers

Despite a career as a helping professional, Phillip Rumrill found himself feeling “inadequate” when it came to caring for his grandmother as her dementia progressed. He admits that he learned how to manage “through trial and error.”

The professional objectivity that allows practitioners to help others process issues in counseling simply isn’t there when it comes to caring for their own loved ones, says Rumrill, a certified rehabilitation counselor and a professor and coordinator of the rehabilitation counseling program at Kent State University.

“All of this stuff that you know about professionally goes out the window when you experience it personally,” Rumrill says. “You may have helped a client who is dealing with this, but it’s not the same when you’re going through it yourself. … You may think that because you have expertise in helping others you might know procedurally what to do, but it’s just different when it’s affecting you on a core level. You can arm yourself with information, but it’s going to be very different to be going through it on your own.”

Although it may not come easily, counselors who have loved ones with dementia should heed the same guidance they would give to clients in the same situation, including keeping up with their self-care and asking for help when needed.

After his grandmother passed away in 2009, Rumrill collaborated with two colleagues, Kimberly Wickert and Danielle Dresden, who also had cared for loved ones with dementia, to write the book The Sandwich Generation’s Guide to Elder Care. Their hope was that their insights might help other practitioners who were facing similar challenges. “You can’t be [your] family’s counselor,” Rumrill says. “Sometimes you have to shut off your professional side and deal with the humanity of your own experience.”

John Michalka, a licensed professional counselor and private practitioner, says he and his wife experienced a range of issues — from stress to anxiety to grief — while caring for his mother-in-law. Michalka’s mother-in-law, who had vascular dementia, moved in with Michalka and his wife in 2013 when she was no longer able to care for herself.

“I took a hiatus from work, and for the last two years of her life, I cared for her until she passed [in January 2015],” he says. “I watched my wife, as a daughter, struggle with pain and grieving during every step down of the disease, from [her mother] forgetting our names to [us] becoming absolute strangers. For me, I was the caregiver and did my best to suppress the emotion. To say the least, caring for anyone living with dementia can be extremely difficult. At least it was for me.”

****

The Alzheimer’s Association has a wealth of information on dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, including nuances of the diagnoses and resources for living with or caring for a person who has been diagnosed. Call the association’s 24/7 helpline at 800-272-3900 or visit alz.org (click the “Help & Support” tab for links to online and local support groups).

Also, the U.S. Administration on Aging offers an eldercare services search tool at eldercare.acl.gov. Resources are also available from the Dementia Action Alliance (daanow.org) and the Family Caregiver Alliance (caregiver.org).

****

Contact the counselors interviewed for this article:

****

Read more

Check out an extended Q+A with licensed professional counselor Ruth Drew, the Alzheimer’s

Association’s director of information and support services, at CT Online: ct.counseling.org/2019/12/qa-helping-clients-affected-by-dementia/

****

I found out about this exciting group from a fragrance advertisement for Hope, Hope Sport, and Hope Night, all available at Bergdorf Goodman.com. All net profits support Hope For Depression Research Foundation.

Learn more at HOPEFORDEPRESSION.ORG

Please check out their site, it’s packed full of information and resources.

Melinda

In 2010, HDRF launched its Depression Task Force (DTF) – an outstanding collaboration of seven leading scientists, at the frontiers of brain science, from different research institutions across the U.S. and Canada. These scientists have developed an unprecedented research plan that integrates the most advanced knowledge in genetics, epigenetics, molecular biology, electrophysiology, and brain imaging. To accelerate breakthrough research, they share ongoing results, in real time, at a centralized data bank, the HDRF Data Center.

HDRF was founded in April 2006 by Audrey Gruss in memory of her mother, Hope, who suffered from clinical depression.

Every dollar raised goes directly to research.

When she passed away in December 2005, I vowed that I would do all in my power to help conquer this dreaded illness. As my mother’s patient advocate, I had consulted with leading psychopharmacologists to better understand her various treatments and medications. I soon discovered the staggering reality that in the twenty-five years since the introduction of Prozac and the other SSRI antidepressants, there has been virtually no change in the basic treatment of depression, just adjustments in the use of existing approaches.

Our mission is two-fold: First and foremost HDRF funds advanced research to find the causes of depression, a medical diagnosis, new medications and treatments and prevention of depression. To that end, HDRF has formed the Depression Task Force — an outstanding collaboration of leading neuroscientists across the US and Canada, each a pioneer in their own field. Together they have created an unprecedented research plan – The Hope Project – that accelerates the research process by sharing ongoing results, in real time, at a new HDRF Data Center.

The second goal is to raise awareness of depression as a medical illness and to educate the public about the facts of depression. We educate and inform in order to help remove the stigma of depression.

The study of depression and the brain is the last frontier of medicine. Your support for HDRF’s pioneering research can make a difference to those you personally know and to the hundreds of millions suffering worldwide.

Although doctors couldn’t find a cure for my mother’s psychic pain in her lifetime, I feel confident that with the progressive direction of our research and the encouragement of “out-of-the-box” scientific thinking, in my lifetime we will make significant strides, providing hope and help to everyone who is touched by depression.

Sincerely,

Audrey Gruss

The block editor allows for a smoother drafting experience – now possible on any screen size.

The Block Editor is Now Supported on the WordPress Native Apps — The WordPress.com Blog

Jan 07,2020

Jeff Grabmeier Ohio State News grabmeier.1@osu.edu |

Study suggests friends don’t encourage them to seek help

When college students post about feelings of depression on Facebook, their friends are unlikely to encourage them to seek help, a small study suggests.

In fact, in this study, none of the 33 participating students said their friends told them they should reach out to a mental health professional to discuss their problems.

Instead, most friends simply sent supportive or motivating messages. Scottye CashBut that may not be good enough for people who are truly depressed – as some of the people in this study probably were, said Scottye Cash, lead author of the study and professor of social work at The Ohio State University.

Scottye CashBut that may not be good enough for people who are truly depressed – as some of the people in this study probably were, said Scottye Cash, lead author of the study and professor of social work at The Ohio State University.

“It makes me concerned that none of the Facebook friends of students in this study were proactive in helping their friend get help,” Cash said.

“We need to figure out why.”

The research, published online recently in the journal JMIR Research Protocols, is part of a larger online study of health outcomes of 287 students at four universities in the Midwest and West. This study included the 33 students in the larger study who reported that they had “reached out on Facebook for help when depressed.”

The students reported what type of post they made and how their friends responded. They also completed a measure of depression.

Results showed that nearly half of the participants reported symptoms consistent with moderate or severe depression and 33 percent indicated they had had suicidal thoughts several days in the previous few weeks.

“There’s no doubt that many of the students in our study needed mental health help,” Cash said.

The two most common themes in the participants’ Facebook posts were negative emotions (“I just said I felt so alone,” one student reported) or having a bad day (“Terrible day. Things couldn’t get any worse,” one wrote). Together, those themes appeared in about 45 percent of the posts the students reported on.

But only one of the students directly asked for help and only three mentioned “depression” or related words, Cash said.

Many participants found ways to hint at how they were feeling without being explicit: 15 percent used sad song lyrics, 5 percent used an emoji or emotion to indicate their depressed feelings and another 5 percent used a quote to express sadness.

“They didn’t use words like ‘depressed’ in their Facebook posts,” Cash said.

“It may be because of the stigma around mental illness. Or maybe they didn’t know that their symptoms indicated that they were depressed.”

Students reported that the most common responses from their friends to their posts about depression (about 35 percent of responses) were simply supportive gestures. “All my close friends were there to encourage me and letting me know that everything will be okay,” one student wrote.

The next most common response (19 percent of posts) was to ask what was wrong, which participants didn’t always take positively. “It is hard to tell who cares or who’s (just) curious this way, though,” one participant wrote.

The other three most common responses (all occurring 11 percent of the time) were contacting the depressed friend outside of Facebook, sending a private message within the app, or simply “liking” the post.

Although participants reported that none of their friends suggested they get help, Cash said she is sympathetic to the plight of these friends.

“For the friends reading these posts, they often have to read between the lines since few people came right out and said they were depressed,” Cash said.

“Many people used quotes and song lyrics to talk about how they’re feeling, so their friends really had to decode what they were saying.”

Cash said the findings point to the need for more mental health literacy among college students and others so they know how to recognize the signs of depression and how to respond.

“Both Facebook and colleges and universities could do more to give these students information about resources, mental health support and how to recognize the signs of depression and anxiety,” she said.

“We need to increase mental health literacy and decrease mental health stigma.”

Co-authors of the study were Laura Marie Schwab-Reese of Purdue University; Erin Zipfel, a former graduate student at Ohio State; and Megan Wilt and Megan Moreno of the University of Wisconsin.

Facebook posts about depression rarely spark friends to suggest counseling, a new study suggests.

IDEAS.TED.COM

Jan 6, 2020 / BJ Fogg

Krystal Quiles

Psychologist BJ Fogg is the founder and director of the Behavior Design Lab at Stanford University — he’s coached over 40,000 people in his behavior change methods and influenced countless more. His Tiny Habits method states that a new behavior happens when three elements come together: motivation, ability and a prompt.

If we really want to make lasting changes in our lives, Fogg believes we need to break them down into specific, easy behaviors (what he calls Tiny Habits), and find ways to trigger and reward them. Taking 30 seconds or less, a Tiny Habit is fast, simple and will grow For example, instead of having “get in shape” as a vague and intimidating goal, do two push-ups every time you make your morning coffee — that’s your Tiny Habit. After a while, you can increase the number of push-ups and expand into different exercises.

In working with thousands of people, Fogg has found one thing really helps fledgling habits to stick: Celebrating them. Here, he explains how the power of celebration can wire new behaviors into our lives — and make us feel great in the process.

Linda had a postcard taped on her fridge next to her kids’ finger-painted masterpieces. It was a black-and-white illustration of a 1950s housewife talking on the phone. Above the woman’s perfectly coiffed head was a talk bubble: “If the kids are alive at five o’clock, I’ve done my job.”

When Linda saw it, she laughed out loud. It made her smile, then it made her think. It represented an attitude of self-acceptance that she badly wanted but felt was too difficult to adopt.

Linda was a full-time stay-at-home mom with six kids under the age of 13. She loved being home and wouldn’t have had it any other way, yet she felt constantly underwater and overwhelmed. Unlike the woman on the postcard, Linda’s every thought at the end of the day was about all the things she didn’t get done or had done badly: the Cheerios on the back seat of the car (“I should have vacuumed it”); the dirty plates in the sink (“I should have washed them; my mom would never left them”); her son’s face falling after she snapped at him for teasing his sister (“I should be more patient”), and so on.

In my research, I’ve found that adults have many ways to tell themselves “I did a bad job” and very few ways of saying “I did a good job.” Like Linda, we rarely recognize our successes and feel good about our accomplishments. We focus only on our shortcomings as we scamper through our days and trudge through our years.

I want to show you how to gain a superpower — the ability to feel good at any given moment — and use this superpower to transform your habits and, ultimately, your life. Feeling good is a vital part of the Tiny Habits method. You can create this good feeling by using a technique I call “celebration.” When you celebrate, you create a positive feeling inside yourself on demand. This good feeling wires the new habit into your brain. Celebration is both a specific technique for behavior change and a psychological frame shift.

I discovered the power of celebration when I was trying to pick up a tooth-flossing habit. I stumbled on it at a time when I felt so much stress that I could barely get through each day. A new business I’d started was failing, and my young nephew had died tragically. Navigating the fallout of those events meant I hadn’t gotten a good night’s sleep in weeks. I was so anxious most nights that I would get up at 3 AM and do the only thing that calmed me down: watch videos of puppies on the Internet.

One early morning, after a particularly bad night, I glanced in the mirror and thought to myself, “You know, this could be the day when the wheels totally fall off.” A day of not just setbacks but paralyzing failure.

As I went about my morning routine, I picked up the floss and flossed one tooth. I thought to myself, “Well, even if everything else goes wrong today, I’m not a total failure. At least I flossed one tooth.”

I smiled in the mirror and said one word to myself: “Victory!”

Then I felt it.

Something changed. It was like a warm space had opened up in my chest where there had been a dark tightness. I felt calmer and even a little energized. And this made me want to feel that way again.

But then I worried that I was losing it. My nephew had just died, my life seemed ready to fall apart, and flossing one tooth had made me feel better? That’s nuts.

If I hadn’t been a behavior scientist and endlessly curious about human nature, I might have laughed at myself and left it alone. But I asked myself, “How did flossing that tooth make me feel better? Was it the flossing itself? Or was it saying ‘Victory!’ into the mirror? Or was it smiling?”

I tried it again that evening. I flossed one tooth, smiled at myself in the mirror, and said, “Victory!” In the days that followed, many of which were still difficult, I continued to floss and proclaim victory. No matter what else was going on, I was able to create a moment in each day when I felt good — and that was remarkable.

When I teach people about human behavior, I boil it down to three words: Emotions create habits. Not repetition. Not frequency. Not fairy dust. Emotions. When you are designing for habit formation — for yourself or for someone else — you are really designing for emotions.

Celebration is the best way to use emotions and create a positive feeling that wires in new habits. It’s free, fast, and available to people of every color, shape, size, income and personality. In addition, celebration teaches us how to be nice to ourselves — a skill that pays out the biggest dividends of all.

Celebration is habit fertilizer. Each individual celebration strengthens the roots of a specific habit, but the accumulation of celebrations over time is what fertilizes the entire habit garden. By cultivating feelings of success and confidence, we make the soil more inviting and nourishing for all the other habit seeds we want to plant.

You can adopt a new habit faster and more reliably by celebrating at three different times: the moment you remember to do the habit, when you’re doing the habit, and immediately after completing the habit. Your celebration does not have to be something you say out loud or even physically express. The only rule is that it has to be something said or done — internally or externally — that makes you feel good and creates a feeling of success. It could be a “yes!”; a fist pump; a big smile; a V with your arms. You might imagine the roar of the crowd; think to yourself “Good job” or “I got this”; or picture fireworks.

I like to call this feeling “Shine.” You know it already. You feel Shine when you ace an exam. You feel Shine when you give a great presentation and people clap at the end. You feel Shine when you smell something delicious that you cooked for the first time.

If you’re stumped on what celebration might work for you, put yourself in the following scenarios and watch how you react. This will give you a clue about your natural ways of celebrating. As you read them, don’t overthink or analyze. Just let yourself react.

Scenario #1: You apply for your dream job. You make it through the process all the way to the final interview. The hiring manager says, “We’ll send an email with our decision.” The next morning the manager’s email is waiting for you. You open it, and the first word you read is: “Congratulations!” What do you do at that moment?

Scenario #2: You’re sitting at work. You have a piece of paper to recycle, and the recycling bin is in the far corner of the room. You decide to wad up the paper and throw it; you are not sure you’ll make it. You aim carefully and toss the paper. Up it goes into an arc and it vanishes into the bin — perfect shot! What do you do at that moment?

Scenario #3: Your favorite sports team is in the championship game. The score is tied and as the time on the clock runs out, your team scores — and wins the championship. What do you do at that moment?

Suppose you have this as a proposed habit: “After I walk in the door after work, I will hang up my keys.” I encourage you to celebrate the exact moment your brain reminds you to do your new habit. Imagine you walk in the door after work, and as you’re putting down your backpack, this idea pops into your head: “Oh, now is when I said I was going to hang my keys up so I can find them tomorrow.”

Celebrate right then. You’ll feel Shine, and by feeling it, you are wiring in the habit of remembering to hang up your keys, not the habit of hanging up your keys. When you celebrate remembering to do your habit, you’ll wire in that moment of remembering. And that’s important. If you don’t remember to do a habit, you won’t do it.

Another time to celebrate is while you’re doing your new habit. Your brain will associate the behavior with Shine. A woman named Jill was trying to adopt the practice of wiping down the kitchen counter right after she used it. What most reliably prompted the feeling of Shine for her was picturing the meal that her husband would make that night and imagining him giving her a kiss and saying, “Nice work, babe.” Her celebration was her visualizing this moment. It allowed her to connect her small action with positive feelings of togetherness. This celebration wired in the remembering and increased her motivation to wipe the counter in the future. Fast-forward to today: Jill wipes the counter without even thinking about it.

I know that celebration can sometimes trip people up. They can’t get themselves to celebrate, or they’ve tried out different celebrations and still feel like a big faker. It also may not feel that compelling or comfortable. If that’s how you feel, I suggest that you try one of my favorite techniques to get a taste of the power of celebration: the Celebration Blitz.

I encourage everyone to do a Celebration Blitz when you need a score in the win column: Go to the messiest room or corner in your house or office, set a timer for three minutes, and tidy up. After every errant paper you throw away, celebrate. After every dishtowel you fold and hang back up, celebrate. After every toy you toss back into its cubbyhole — you get the idea. Say, “Good for me!” and “Wow. That looks better.” And do a fist pump or whatever works for you. Celebrate each tiny success even if you don’t feel it authentically, because as soon as that timer goes off, I want you to stop and tune into what you are feeling.

I predict that your mood will be lighter and that you will have a noticeable feeling of Shine. You will be more optimistic about your day and your tasks ahead. You may be surprised at how quickly you’ve shifted your perspective. You’ll see that you made your life better in just three minutes. Not just because the room is tidier, but because you took three minutes to practice the skills of change by exploring the effects of tiny celebrations done quickly.

Excerpted from the new book Tiny Habits: The Small Changes that Change Everything by BJ Fogg. Copyright © 2019 BJ Fogg. Used with permission from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Watch his TEDxFremont Talk here:

BJ Fogg , PhD, is the founder and director of the Behavior Design Lab at Stanford. In addition to his research, he teaches boot camps in Behavior Design for industry innovators and also leads the Tiny Habits Academy helping people around the world.

I’m so glad you stopped by today. I appreciate you and so glad to be a part of your day. Melinda

Here are the rules for SoCS:

Have a great day, I wish you could see the smile on my face! Thanks for stopping by today. Melinda

By Diane Cleverly, PhD, Founder of Concierge Conversations

Not only that, but Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements per patient have dropped. That means physicians are increasingly pressured to see more patients per day.

What does this mean for you, the patient? For one thing, your doctor has basically taken a pay cut. So it’s more important than ever to walk into a doctor’s appointment prepared in order to help you connect with your doctor on a personal level.

But we all know that pain interferes with communication. It may cause you to get less sleep, or take meds that make you a little foggy; both of these can affect cognition. Pain is subjective—it’s hard to talk about even in the best of circumstances. So how can you ensure that you and your doctor understand each other?

Doctors will often ask you to describe your pain intensity on a scale of 1-10—with 1-3 being pain that doesn’t bother you much at all and 9-10 constituting an emergency. But people with chronic pain often downgrade their pain—in part, because you’re so used to dealing with it that it doesn’t register the same way it might for someone who’s just stubbed their toe.

A good thing to remember when using the pain scale is that giving a range of numbers can also be very helpful to your doctor: “Well, I woke up at a 3, but after grocery shopping I was at a level 7.” Go into detail—at what level do you typically take medication? At what level do you call your doctor?

A crucial way to communicate your level of pain with your doctor is to talk about the functional impact it has on your day-to-day life. You may know how pain has changed your life in a larger sense; how it’s made you a different person, or caused you to give up activities you loved. But your doctor doesn’t. Here’s a little secret: When you talk about what the medical community calls “daily activities of living,” doctors often sit up and take notice.

So here are some specific things you should discuss with your doctor:

If you tell your doctor you’re having trouble with any of these things, it often will trigger them to investigate further.

The other important piece to keep in mind when talking to your doctor about your pain is communicating your short- and long-term goals.

Here’s where the pain intensity scale is crucial. State clearly to your doctor, “My short-term goal is to go from a pain level of X to a pain level of Y so that I can resume [working, cleaning my house, driving, etc.]”

Explain the timeframe you have in mind. “I’d like to feel a difference within four to six weeks.” Now, depending on your disease state, this may not be possible, and you can negotiate that with your doctor. But it’s important to set a short-term goal, and to target getting your pain levels below a 5—which typically means an improvement in function.

Ask your doctor, “What will it take to get me there?”

Next, move on to long-term goals. This may be simply getting the right diagnosis or it could be getting back to work (the number one thing most pain sufferers want). It may mean coming up with a long-term pain management plan or a strategy to reduce your risk of relapse. Whatever it is, communicate it.

Complementary therapies such as acupuncture, therapeutic massage, biofeedback, medical marijuana, or chiropractic care can be a touchy subject with some physicians—though they shouldn’t be. Ask your doctor in a nice way, “Would X therapy be helpful in achieving my short-term goals?” or “Do you think I could try X therapy along with standard therapy to manage my pain better?”

Your physician might even have other suggestions and resources for complementary medicine, so don’t be afraid to ask.

Above all, it may help to change the way you think about your doctor’s visit. It’s not a social call; it’s a business meeting. Keep your goals top of mind and stay focused. Set goals, track their progress, and refer back to them to assess your improvement over time.

If you need further guidance, visit personalhealth4u.wordpress.com.

Diane Cleverley, PhD, is currently creating regulatory submission materials for clinical trials as a senior medical writer for Synchrogenix, as well as helping patients improve their communication with physicians to get better healthcare. Dr. Cleverley graduated with a PhD in microbiology and molecular genetics from Rutgers University. She has spent time with patients the past 25 years in healthcare and patient education. Dr. Cleverley has also been an adjunct professor for a number of colleges and universities, most recently Southern New Hampshire University, teaching a course in Health Literacy.

| Dear pain warriors, You’ve probably heard of yoga before and thought to yourself “there’s no way I could do that!” But you may not realize that there is a style or type of yoga for every level and ability. Gentle yoga, for example, is perfect for individuals with chronic pain and disability. There are plenty of options and modifications–you can even participate sitting in a chair! We’re excited to offer you a chance to explore yoga from the comfort of your home on Tuesday, Jan. 21, at 1 pm EST during a free interactive class and live Q&A with Ryan Drozd, a yoga instructor and wellness expert. Drozd lives with chronic pain himself, so he’s well-versed in helping find movements that are right for you and your body. Register now >> We hope you can join us live, but if not, all of our webinars are recorded and posted within a few days on our website. If you have questions, email contact@uspainfoundation.org. If you have specific concerns about the safety of yoga for your health situation, please check in with your health care provider. Sincerely, Emily Lemiska Director of Communications U.S. Pain Foundation |